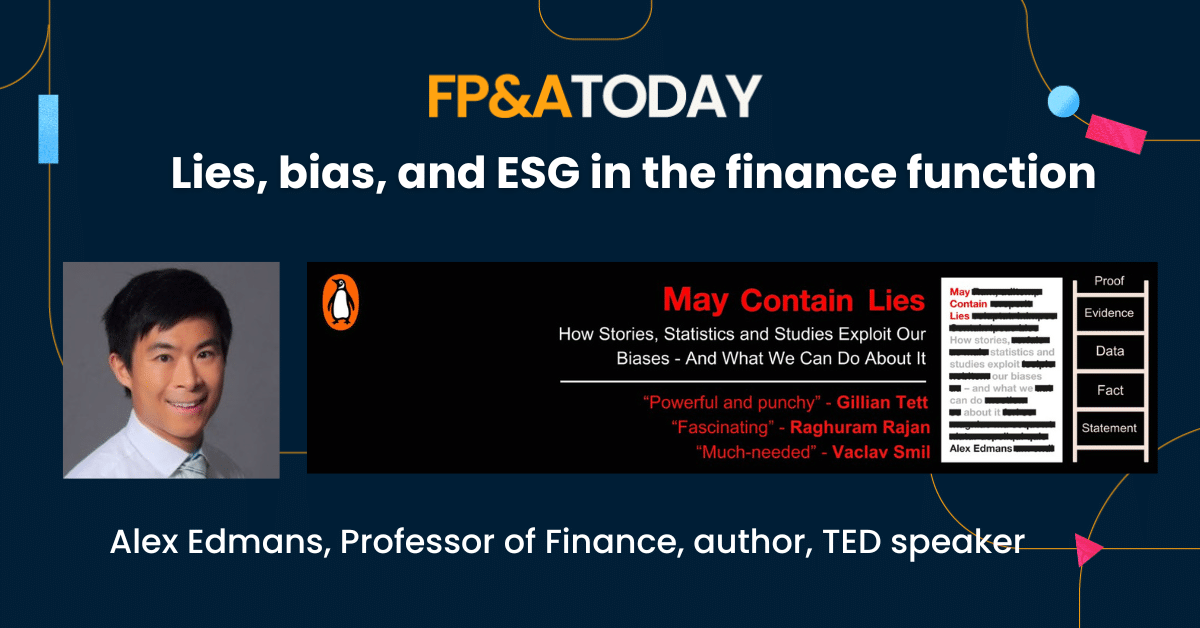

Alex Edmans is a professor of Finance, non-executive director, author, and TED speaker. He is regularly interviewed and writes for WSJ, Bloomberg, BBC, CNBC, CNN, ESPN, Fox, ITV, NPR, Reuters, Sky News, and Sky Sports. He was previously a tenured professor at Wharton and an investment banker at Morgan Stanley.

In this episode we talk to Alex about his new book “May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases – And What We Can Do About. He is also a co-author of the classic text book, “Principles of Corporate Finance” and top business book (his first book) Grow the Pie, How Great Companies Deliver both purpose and Profit. His Ted Talk on what to trust in a post truth world has alone been viewed nearly 2m times.

So many thought-provoking takeaways for anyone in FP&A!

- Leaving Morgan Stanley to become a professor of finance

- Why I give Ted Talks rather than just publishing research

- How CFOs and FP&A leaders can think about purpose

- Is ESG a tick-box exercise for finance?

- How FP&A and finance leaders can check their biases

- How you can control your addiction to bias

- Silicon Valley Bank and why financial models were affected by bias

Follow Alex on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aedmans/

Links to Alex’s new book:

May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases―And What We Can Do about

TED: What to trust in a “post-truth” world

Full transcript

Glenn Hopper:

If you would like to earn CPE credit for listening to the show, visit earmark cpe.com/fpe. Download the app, take a short quiz, and get your CPE certificate. Finally, if you enjoy listening to FPA today, please go to your podcast platform of choice. Click the subscribe button and leave a rating in review of the show. And now onto the show.

Welcome to FP&A Today, I’m your host, Glenn Hopper. Today we welcome Dr. Alex Edmans to the show. Alex has a PhD in financial economics from MIT where he was a Fulbright Scholar. He’s a professor of finance author and Ted speaker. He is regularly interviewed and writes for the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, BBC, NPR, and Sky News, among others. He was previously a tenured professor at Wharton and an investment banker at Morgan Stanley. In this episode, we talk to Alex about his new book May Contain Lies, how Stories, statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases and what we can do about it. He is also a co-author of the classic Textbook Principles of Corporate Finance and Top Business book, which was his first book, grow the Pie, how Great Companies Deliver both Purpose and Profit. His TED Talk on What to Trust in a Post-Truth world has been viewed nearly 2 million times. Alex is a fascinating business leader and academic, and we’re excited to have him on the show today. So Alex, welcome to the show.

Alex Edmans:

Thanks so much, Glenn, for having me on.

Glenn Hopper:

Yeah, fascinating background and uh, I covered a lot of it in in the intro, but kind of in your own words, walk me through your, your career and how you got and, and books that you’ve put out and tell me about your background and, and where you are and where your passions are today.

Alex Edmans:

So I studied economics and management at Oxford University and I pursued a boring career, the career that everybody pursues if you do that degree, which was, I went into the city. So I was an investment banquet Morgan Stanley for a couple of years, but then I did an unusual route. I I left that to become an academic, to be a professor of finance. I did a PhD at MIT and then was a professor at Wharton before moving to LBS. So that is bizarre. So why would you give up this highly paid prestigious job to be a poor academic? Um, I actually liked my job at Morgan Stanley. So many people get beaten up and mistreated and yeah, I did have to work long hours, but generally I thought I was working on interesting stuff. However, I would work on one company’s problems at one time.

So I remember when I completed my first deal, that was great, right? The next day, the Financial Times front page was about that deal, but then the following day it was on something else and I thought, well, I’ve spent seven months of my time on this one thing that affects that one company. Whereas as a professor, if you write a book or give a TED talk, that could be seen by millions of people. So the bandwidth of your impact could be much higher. And also what you might be contributing could be more timeless. So if you find, say, a link between social responsibility and profits, that could be true in 2025 as much as in 2011 when you first published the paper. So for that reason, I, I moved into academics, but I’m a rather unusual academic in that I don’t like just doing research to sit in the library. I really like the implications for practice in a general audience, which is really, I I’m really grateful to be on podcasts like this to a address, a practitioner audience.

Glenn Hopper:

I do wanna talk about your books. Your first book I believe was Grow the Pie, and that’s how great companies deliver both purpose and profit. And I think that’s an interesting approach, and I think you were a bit prophetic because I’m hearing more people talk about that today maybe than, than we have in the past. Because, you know, the, the business school, what you learn there is, uh, you know, the, the goal of a company is to maximize shareholder value and just profit, profit, profit. But adding that purpose to there is a key element and you are seeing more companies embrace this. Now, can you walk us through that approach a little bit?

Alex Edmans:

Absolutely. So, so why did I choose to write that book? It was about the debate on purpose or profit, but I thought that this debate was rooted in the wrong paradigm. And what is that wrong paradigm? It’s that word or purpose or profit. So on the one hand you have people saying, well, the goal of a company, companies just to maximize profit, all of these purpose, uh, pressures, these are just woke. Let’s not cave into them. That’s why, at least in the US there’s some, let’s say, supporters of big business who believe that these things are a distraction. But on the flip side, you have supporters of say society and the economy who argue that companies are evil and profits are evil. But I don’t need to tell a finance audience that this is not true. Right? How do companies make profits in the long term by making great products, by treating their customers well, by having a great reputation for environmental preservation.

So this is why the book is called Grow the Pie. So many people have a fixed pie mindset. The value that a company creates is given by a pie that can be shared for between investors in the form of profits and society in the form of fair wages, taxes, and prices. And if we think the pie is fixed, then purpose is at the expense of profit because the greater slice you give to society, the less there is for investors. But I’m saying no, the pie can be grown. And this is not just based on wishful thinking, but a lot of academic research is that if a company is delivering value to its society, if its treating its employees well investing in human capital, ultimately it’ll become more profitable. And I think this is really important because some people view finance as the enemy of ESG is because finance is so focused on the numbers, they will turn down ESG initiatives.

Well, that might be true if you have a short term focus on the numbers, but anybody with a long term focus on the numbers realizes that these things might be actually complimentary. If I was the CFO of a car company, would I want that car company to develop electric cars? Well, absolutely. Even if I don’t care about climate change, I know that electric cars could be the future and therefore I would be willing to allow these companies to invest in electric cars. Not because it’s woke, not because it’s good for the environment. Yes, at the end of the day, I need to make money, but these things can be a route towards making money. So I wanted to change the narrative, the divisive debate between purpose and profit and say, in many cases, ESG can be beneficial for why, for, for the company’s long-term performance.

Glenn Hopper:

ESG is such a, a complicated area right now for fin you know, finance taking on and just the nuts and bolts of doing it and the regulation around it. Do you see the dictated ESG working or is it more, it’s not just checking a box. It it is how much is incumbent on the companies themselves to really lean in and have that purpose follow versus just checking the box of going through and ESG compliance?

Alex Edmans:

I absolutely agree with you, Glen. Is is that EESG should not be a compliance exercise. It should be something that you do because fundamentally you believe it will improve long-term financial performance. So I give this following example. So let’s be concrete and give some real world examples. So in in 2007, Vodafone, which is a UK telecoms company, it launched Empeza, which is a mobile money service in Kenya. It allowed people to transfer money from phone to phone just as easily as you could send a text message. Now that transformed people’s lives. So within the first seven years it lifted 200,000 households outta poverty by giving them access to finance. And also many of these households were headed up by women. It allowed them to move from agriculture to business and retail. So there’s a big social impact, but also Vodafone is able to make a profit from it because it can charge a small percentage of every transaction as a fee.

Now does that tick any ESG boxes? Well, probably not. It doesn’t reduce its carbon footprint, it doesn’t reduce its gender pay gap, it doesn’t reduce its water usage. And there’s many people who think, well, ESG is about risk management, let’s do ESG to ensure that we are not Wells Fargo or um, Volkswagen. But if Vodafone had not launched Empeza, nothing would’ve happened. So there would’ve been no media backlash, there would’ve been no customer boycott. So instead of thinking about ESG as a cost center, let’s do the minimum possible to tick boxes so there’s no, no outrage, let’s get on the front foot. Let’s see this as a profit center. If we’re a company who can be inspired by things that create value for society, ultimately some of that value might come back to us in the form of of profits. And so this is why I’d like to have a much more positive view of ESG to be on the front foot to do something, even if you couldn’t tell anybody about it.

So one question I ask companies is, if you could not tell anybody you were doing it, would you still do it? And I think that’s important. Would you still develop a diverse and inclusive workforce with psychological safety? Yes, I would still do this, but that’s different from other companies’ approaches to DEI, which is let’s make a particular DEI higher in order to tick the box that I have sort of ethnic diversity on the board, even if the ethnic minority brought in might be somebody like me who has a finance background and might not actually provide any diversity in terms of skillset.

Glenn Hopper:

Thinking about the companies that you work with or whether you’re talking to students or companies or, or even people through your book, do you notice in talking with more established maybe older <laugh>, and I’m not, maybe I’m throwing too some ageism in here, but I’m thinking of of sort of established and people who’ve been in business versus younger people just coming up studying this right now, the receptiveness to it. The reason for this question is I feel like the more you get set in a way of doing business, where if you really, and especially in finance, it’s so hard, so hard to keep that broad view because you can get so focused on, you know, these are our, our ratios that we’ve gotta hit and these are the numbers we’ve gotta hit. And, and when you throw in, especially when it comes in through the door of this is a requirement, not a company culture, I wonder if it’s hard for existing companies to shift more towards that mindset. Um, and then conversely, if you’re seeing people, maybe you know, students who haven’t gone out into the business world yet, if you’re seeing them more receptive to it and they’re kind of carrying this with them as an ideal before they even enter the workforce,

Alex Edmans:

Lots of great layers to that, that question, lemme try and unpack them. So first, can a company shift its view of that company’s been there for a while and so this is why a lot of my research has been trying to show that it’s in your own interest as a company to embrace sustainability. So I come to this problem as a finance professor, as an ex investment banker who understands the need to generate profit. I’m not saying do it because it’s good for the environment or because we need to save the dolphins. Those are important things, but I understand commercial reality is that we, we, we need to, to to make a profit. So I’m not trying to guilt trip companies to do this or to say, you have a moral obligation to do this because why are my models better than anybody else’s models?

Why don’t you have a moral obligation to deliver high returns to your shareholders who might be pensioners who, who need to fund their retirement? So instead I’m saying it’s not about morals and ethics, it’s about what is commercially successful and sensible. And indeed the evidence suggests that many companies who are investing in material ESG issues are performing better in the long term. And so that’s what I would say to established firms. And I, we do see a movement in, in this direction, and the people I speak to mostly are finance people, given my background, who many people would accuse as being the enemy of sustainability. But that, that’s unfair. Uh, many of them are not. They are embracing this. Now you asked this generational question, and it certainly is true, um, that, uh, the current generation of students is much more receptive. So when I started as a professor at Wharton in 2007, if I was to speak about sustainability or purpose, probably students would’ve laughed their way out of the room and said, why do we have this person here teaching us big business nowadays?

There’s a lot of excitement, but I think that excitement sometimes can be too far the other way, which is people focus only or predominantly about the ESG of a company and forgetting about the nuts and bolts. So if you are a company, provide a great product, have great customer service, and that to me, I care about much more than how many charit organizations you, you gave, right? If I’m taking a a, a plane, let make, let’s make sure that the planes are flying on time, that there’s good customer service, and that when I call them somebody picks up. Um, sometimes people will focus on the composition of the board and issues such as that, um, which unless it directly feeds through into decisions that affect customers might not be as, as as relevant. So one of my influential articles from a couple of years ago was called The End of ESG, and you might think that’s crazy.

How can someone like Alex write an article or called the end of ESG because he’s an ESG advocate. But I’m saying the end of ESG in two ways. Number one, as a niche field, which is of interest only to ESG people. I’m saying it shouldn’t be called ESG because a finance person should care about ESG issues, their financial material. But I also talked about the end of ESG as a topic to be put on a pedestal. For some reason, ESG is seen as a magic word that we would boycott a company because it has bad ESG, we’d invest in the company only because it has good ESG. I’m saying ESG is one of many factors that matter. The first line of that article was ESG is extremely important and nothing special. So it’s extremely important. It drives financial value, but it’s nothing special. It should not be on a pedestal compared to other things that drive financial value as well.

Glenn Hopper:

Got you. Well said. Fp and a today is brought to you by Data Rails. The world’s number one fp and a solution data rails is the artificial intelligence powered financial planning and analysis platform built for Excel users. That’s right, you can stay in Excel, but instead of facing hell for every budget month end close or forecast, you can enjoy a paradise of data consolidation, advanced visualization reporting and AI capabilities, plus game changing insights, giving you instant answers and your story created in seconds. Find out why more than a thousand finance teams use data rails to uncover their company’s real story. Don’t replace Excel, embrace Excel, learn more@datarails.com.

This is maybe a typical finance person question to ask you, but what if I could have the best of both worlds? And I’m wondering if any of your research has shown that. Do you see instances where companies that do have a purpose and that are, uh, not just focused on the bottom line, that are focused, you know, on society, on the whole, on their employees? Are you seeing companies that have this mindset and mentality and approach actually having better returns or, or performing better maybe than companies that don’t? Is there any research to back that up or is, is that too much of a pipe dream <laugh>?

Alex Edmans:

Yes, and this is my own research, and actually this is why I, I got into the topic of sustainability. So I never set out to be a sustainability person. I was doing a PhD in finance, uh, uh, at MIT. Um, and because it was MIT, all of my classmates were looking at quantitative data-driven factors. But I had just been at Morgan Stanley and I, I’d realized that the most important asset is human capital. Uh, it really mattered how you were treated and logically it shouldn’t matter because you were paid so much and you were offered so much in terms of bonuses and promotions. It shouldn’t matter how a boss treats you because the financial incentives were so high, but it did matter. Well, at the end of the day, you were human and if you were treating a certain way, it didn’t matter how many carrots were thrown in front of you in terms of your promotion to associate and vice president, you, you were more or less productive depending on, on how you’re treated.

So I looked at the link between employee satisfaction and long-term stock returns, and I measured employee satisfaction by the list of the hundred best companies to work for in America. Those are companies that go above and beyond in how they treat their peers. And what I found was that over a 28 year period from 1984 to 2011, so it importantly included things like the internet bubble crash, the the financial crisis. I found that these companies beat their peers by 2.3 to 3.8% per year over a 28 year period. That’s 89 to 184% compounded. So simply put companies that treat their workers better, they’re not just fluffy, they’re not just woke. They are being sensible. They’re investing in their most important asset. And as we know, correlation does not imply causation. So I had to do a lot of other tests to show that its employee satisfaction that causes better financial performance rather than better financial performance, allowing a company to invest in its employees. And so that’s something that’s one of many studies in, in, in the, um, grow the pie book. But it is really important to have empirical research behind this. And that’s why that’s my day job as a finance professor is to do research. Otherwise, if this idea was based on a couple of handpicked cherry picked examples, then there would not be some data behind it.

Glenn Hopper:

Data that brings me to your newest book and I’m, I’m excited to, to talk about this one may contain lies how story statistics and studies exploit our biases and what we can do about it. Because I think we are, you know, in in finance and, and the rest of the world, we’re drowning in data right now. And I think finance people in particular, there’s a, it used to just be, you know, this, this concept of you run the numbers, report the numbers, and you’re the, you know, the, uh, unbiased, uh, reporter. But really we all have our own biases and we also all have a story we’re telling. And in finance and fp and a right now, there’s a lot of talk about we are storytellers. So it’s not just make this bar chart, make this histogram. We are actually, you know, we are, we’re trying to convey a message and that’s where we’re adding value. So I think that, you know, there’s that, the old quote about lies, dam lies and statistics, and you can just like in editorializing in newspaper by the, uh, uh, stories that you choose to run, you can editorialize in your, in your reporting around, um, by just the, the numbers that you choose to present to sort of craft your story. So there’s, you know, there’s sort of positives and negatives to the storytelling telling side, but tell me the background of a book and, and why you thought it was important to, to write this right now.

Alex Edmans:

Well, thanks very much for asking about that book. So, so as I mentioned at the start, um, I was somewhat unusually as a professor, I really like to speak to a real world audience. And so I would often present the findings of research to investors or executives or policy makers. And, and what I found was how people would respond to that message depended on whether they liked the message, not whether the evidence behind it was accurate. So if there was an academic study showing something they, like, they would say, oh, this is the world’s best evidence. And if it was a study that people don’t like, they would dismiss it as being just academic research, which has no relevance to the real world. So then I thought, well, this is a problem, is that we are blindsiding ourselves. If we only look at stuff that we agree with, then this might be blinding us to more important issues.

So again, let me give a concrete example. So there’s loads of studies out there claiming that demographic diversity improves financial performance. So Harvard Business Review publishes articles on this. McKinsey publishes studies claiming that, oh, if you just increase the gender or ethnic mix of your boardroom profits will will shoot up. And this is something that I, as an ethnic minority, I would love to be true, but actually the evidence is, is really weak. They make some of the most basic errors, just to give an example of how basic an error is. So what McKinsey does is they relate financial performance in 2017 to 2021 to diversity in 2022. So if anything, it’s financial performance leads to diversity, not diversity, leading to financial performance. But they’re obviously gonna sell that latter story because that’s what goes with, with, with the times. And, and we know that correlation is not causation deep down, but if we like the story being paraded, we accept it uncritically.

And so why does this matter for a person in a finance function, right? We’re always trying to do things that improve the financial performance of the companies that we run. And there’s so many studies out there claiming X improves financial performance, so let’s do more, more of X. But a lot of these studies are actually very, very weak. But because they prey on confirmation bias, they suggest doing good things like demographic diversity, that’s something that helps you, then we accept it uncritically. And you might think, well, I don’t want to argue against this because I would be said to be anti diversity if I was to say, well, there’s problems in this study, but why I think it’s really important to to, to be careful about the data is for the following reasons. So what my own research suggests is diversity does improve financial performance, but it’s not demographic diversity, but it’s cognitive diversity.

It, it’s the diversity of thinking. And what is the difference? Well, a white male is never demographically diverse, but can provide a huge amount of cognitive diversity. It could be that his expertise as in engineering and everybody else as in finance, maybe he grew up in in in a different country, maybe he served the Peace Corps in a foreign, um, country and so on. And so that broader measure is correlated with performance. And so it’s not that I’m anti diversity, I’m actually pro diversity, but the reason for being careful the data, it’s to look at, well, what actual dimensions of diversity are really, really important? And these are things which are really practically key, particularly if we want to improve the profitability of our company.

Glenn Hopper:

So thinking about our biases and they influence us on fire hose of data that comes from Twitter and social media versus whi which news outlets we choose to get our stories from. And then internally in the companies that they can be on sales could have one version of the truth that is explaining why their sales numbers are down. And and maybe ops has a different version of the truth in that, well, we’re not delivering the product properly or whatever the case is. And I’m thinking as we’re receiving all this information, be it from internal sources or from the world at large, and you know, the, a big part of your book is and what we can do about it. So what is, as an individual, like our thinking process, how do we approach and dissect the truth and discern the truth out of, out of these messages?

Alex Edmans:

I think it’s to recognize our own biases. So, so with an addiction, the the first solution to having an addiction is to recognize that you have an addiction. And I don’t think it’s hyperbole to suggest a bias is an addiction. So confirmation bias is we are addicted to believing our view of the world and we dismiss things that, that contradict our, our our viewpoint. And so what this means is that once we realize that we have this bias, we will try to actively seek dissenting viewpoints and try to take seriously things that are shaking us out of our worldview. Again, let me give an example. Silicon Valley Bank, there there were some internal models which predicted that the bank would be in real trouble if interest rates rose. And so some finance people didn’t want to believe this, so they just changed the assumptions of the models.

They basically knew what answer they wanted the model to give, which is the bank is safe. And so they reverse engineered the inputs to give us that result. But this is, it’s highly problematic if the model does suggest that there are problems, um, that might arise, take it seriously. I’m not saying always be a slave to the model. Maybe one possibility is that the model’s assumptions could be wrong, but that’s not the only possible explanation. Uh, take seriously the issue that maybe it is right. Maybe you could benchmark your positioning in government bonds versus other banks and and do other things to try to crosscheck is the model actually correct rather than immediately dismissing it. And then you’re saying, well, if, if, if say operations gives you a different message, then rather than saying, well, operations are wrong because their operations and we’re financed, we know finance better, can we actually get some input from this different viewpoint? And this goes back to why my research find that cognitive diversity is actually what is useful, not demographic diversity, because we have different viewpoints in an organization than that can alert us to what our blind sports might be.

Glenn Hopper:

And I wanna link this in the, in the show notes too, but your TED talk on what to trust in a, in a post-truth world, I think this had like 2 million views to date on that. And I think that, you know, that goes along obviously with, with the book of of May contain lies. What are the takeaways from your TED talk? What are the key things that you would tell your listeners that they could trust in a post-truth world?

Alex Edmans:

So I think the first thing to be careful of is, is confirmation bias is that we all have our biases and we include me. So in in my book, I, I am very upfront about certain things that I incorrectly believed in because I wanted to be them to be true. And so what that means is that we will just latch onto something uncritically because we want it to be true. And so what that means is perversely something which is against our viewpoint and actually, which might be counter-cultural, that might be correct because often people’s incentives are to publish whatever cells and whatever cells is gonna be with the zeitgeist of the time. So I wrote in the book about how I, um, went to a talk on Brexit. So this was in 2016 when the UK was, uh, voting to leave the European Union. I thought we should definitely remain in the bubble that I live in, all believed in remaining in the European Union.

So I went to talks by Brexiters on why we should leave. And, um, I was shocked by how logical their arguments were. Now I didn’t agree with the conclusion, but I could at least see some logic behind where they were getting to. And, and this gave me a very, very different, um, viewpoint. Obviously, I i I don’t know much about the us uh, as an outsider, but certainly what I see from some commentary is why might the Democratic party have not been successful in the, the recent election is perhaps thinking well that Trump supporters are a basket of deplorables, uh, to use Hillary Clinton’s phrase and not understanding the other side. So there are almost always two sides to every story and try to, um, explore the other side. You don’t have to agree with it. Maybe 90% of what you see you might think is nonsense, but maybe if 10% of what you see is actually valid, then you come away smarter than, um, what you did before.

Now clearly we don’t wanna take this to the opposite extreme and say you want to believe in every possible conspiracy theory out there because every conspiracy theory is countercultural, but c is the argument, just listen to the argument to begin with. And c is it based on fact and logic, which I found was the case for the, uh, Brexit arguments. But do I see any evidence that the last election was stolen from Donald Trump? I don’t. So even though I was willing to sort of hear this, I didn’t see any evidence behind it. So I then will dismiss it afterwards. But I did see first whether there was evidence before dismissing it.

Glenn Hopper:

Yeah, I <laugh> a couple of thoughts on that. So first, as as you were describing that, I was thinking of the movie The Mockumentary from the seventies or eighties, however long ago it came out. Uh, this is Spinal Tap and the lead character is kind of adult, uh, musician, and he says, <laugh>, um, I believe everything I read and I think this makes me a more discerning person, which I thought was <laugh> just a really funny line. But, um, I think that issue we have right now is in, in, in the US and I think probably, uh, around the world as, as extremes surface in all areas as as seen kind of in Brexit as well. But when you’re so polarized politically, people don’t want to, they get in that echo chamber of just hearing what, you know, goes along with their confirmation bias that just that positive feedback loop and they don’t open themselves up to the other side because everything seems so extreme and it’s so black and white.

There’s, you know, the pendulum is either swinging in, in either direction in, you know, to the extreme and there’s no, no more meeting in the middle. So I think that’s the hard part is saying, okay, I I may not agree with what is on Fox News and the US or I may not agree with what is in the New York Times or whatever. And, and I may not trust the, the news outlets to who are presenting the news that I don’t even believe what’s in them. So it’s, it’s very hard to overcome that. I don’t know if you’ve got any specific advice for such extremes, but I I think for both sides it’s hard to, to read the other side.

Alex Edmans:

Yeah, so there’s two key biases that I explore in the book. One of them is confirmation bias, which is already discussed, and the second is black and white thinking, which is the tendency to view the world in black and white terms. Something is either always good or always bad. So Democrats are always good, let me believe everything a Democrat says, and Republicans are always bad, but in the real world, there are are shades of gray. And I, I want these issues are really complex. If improving financial performance was as easy as put more ethnic minorities on the board, then everybody would do it. And any company without a diverse board would underperform and go out of business. But things are much more complex and often people see things in such black and white terms. And anybody who even was to raise a concern about the issue with the diversity evidence is labeled as a racist or a sexist when we could be, again, we could be after the same goal, but realize that actually we want to not reduce a person to their gender and ethnicity.

There’s so many other things, uh, about a person which we want to take into account, such as their background, uh, on something like net zero and climate change. We think this is black and white, the world will blow up if we don’t address climate change. But there are other issues out there. So I’m a member of the World Economic Forum, global Future Council that our recent meetings, um, in Dubai, um, we were discussing a just transition and then a woman got up and she said, I’m from Africa. In Africa, 600 million citizens do not have access to electricity. You westerners are speaking about a just transition, but 600 million of my fellow citizens have nothing to transition from. And so to us, net zero is black and white, right? We wanna combat climate change should there even be any other thing we care about? And the answer was yes, the fact that these people don’t have electricity.

And I think recently there was a hospital in Sierra Leone, which will use solar power, and then there was a power cut and then a baby died in a neonatal unit. So, so even in issues which are quite a motive like climate change, which i, I I passionately believe about, there was another side. And I think once we realized that the world is much more complex and nuanced and often portrayed by 280 character tweets, then we are more willing to hear, hear a different viewpoint and a different viewpoint is not necessarily something to argue against, but it might be something to learn from.

Glenn Hopper:

Well stated and great advice. I feel like we could talk all day. I know we, uh, we’re up up against time here and I just, before you go, I know you, you are a regular contributor to, uh, wall Street Journal and, and Reuters and several other places, but for our listeners who want to, uh, follow you and learn more, what’s the best way for them to, uh, to be in, in touch with you? Well,

Alex Edmans:

First thank you. If you are interested in, in following my stuff. So I’m on X and LinkedIn under a Edmans, that’s -E-D-M-A-N-S. And what I try to do here is present, um, complex research, but in simple language practitioner, um, terms and make it as accessible as possible. And I also don’t just post my own research, but research by other academics or research by other institutions. And sometimes I post stuff that I actually disagree with, which, which, which, um, goes against my viewpoint. But because I think it was something that enlightened me because it taught me something new in an issue that I myself have thought of as black and white, I’ll try to share that as well. So I’m trying to make research available to a general audience even if it wasn’t by me and even if it’s not supporting my own view on an issue.

Glenn Hopper:

Well, Alex, thank you so much. It’s, uh, for your insights and it’s, it’s been a, a great episode and we really appreciate you coming on.

Alex Edmans:

Thanks so much Glen, for hosting me.