Officially, the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants defines a budget as a “quantitative expression of a plan for a defined period of time.” This rather dull definition, does not do justice to one of the most vital processes in corporations. Fierce debate about this business staple’s exact purpose still rages. The budget was born from a rich history of government and business titans, while their finance successors today are seeking to revitalize what has become a more plodding process in present times. In this post we look at the origins of the budget, its present, and its uncertain future.

The origin of budgets 1760-1920

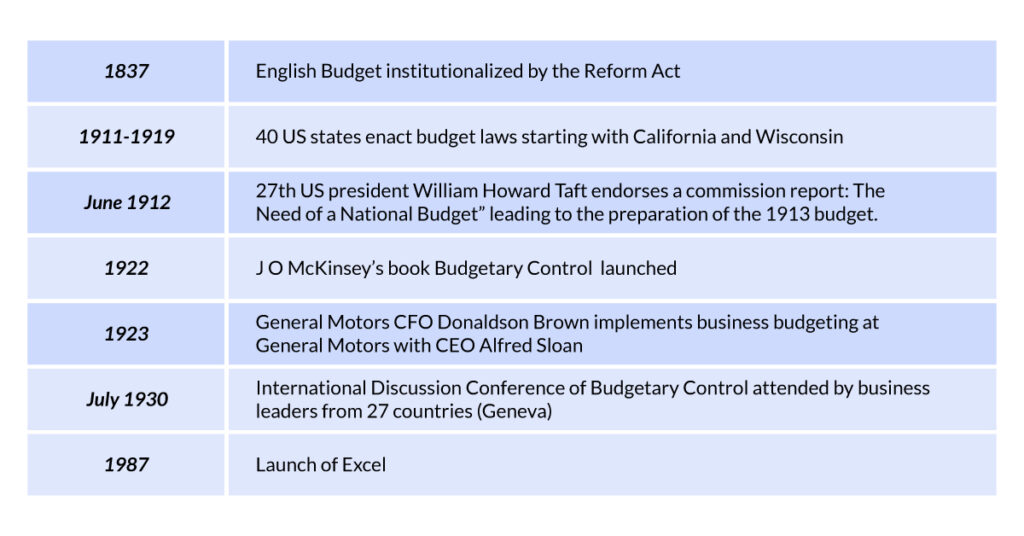

The English word budget is derived from the Latin word “bulga” meaning a leather bag or knapsack used for carrying supplies of food. Later, budget was extended to mean not merely the container but also the thing it contained. The budget began in England. As early as 1760, the Chancellor of the Exchequer presented the national budget to Parliament at the beginning of each fiscal year. The purpose was to check the king’s power to levy burdensome taxes and control spending of money by public officials. In 1837 the budget was made effective by the Reform Act.

The birth of the business budget 1920-1930

It was a similar government-led origin story across the Atlantic that first launched the business budget in boardrooms across the world.

The first US president to lobby for a government budget was 27th US president William Howard Taft. In July 1911, budget forms were prepared and approved by the President. Like with the majority of today’s business budgets, these forms were sent to department heads, to be filled in by them and returned by November 1 1911, however they were not returned until early in June 1912. Nevertheless Taft endorsed a commission report: The Need of a National Budget” leading to the preparation of the 1913 budget.

Between 1911 and 1919 40 US states enacted budget laws starting with California and Wisconsin.

The launch of business budgets: The Titans of planning

Though started in government, the origins of the business budget began with US business titans. The roll call of legends included James O McKinsey (June 4, 1889 – November 30, 1937), Donaldson Brown (1885-1965), Alfred Sloane (1875-1966) and in a different generation, Marvin Bower (1903 –2003).

The first business budget: General Motors

Donaldson Brown was a pioneer of the business budget at two companies, DuPont, and more famously, as CFO at General Motors under legendary CEO Alfred P. Sloan.

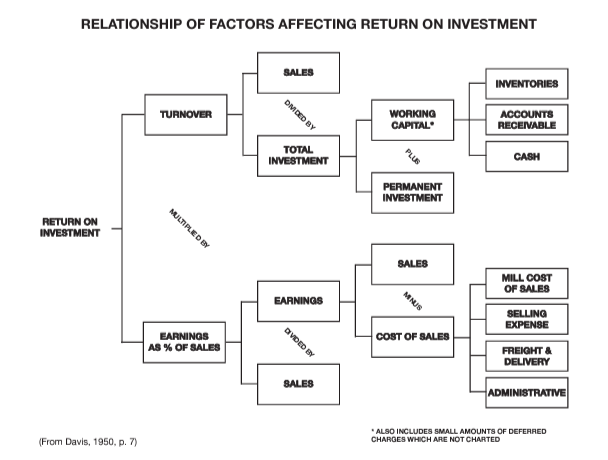

In 1914, Brown, a genius in finance, was asked for a report on the performance of several operating departments at polymer-developer DuPont, a large American conglomerate. It was at this point that he developed the procedure now known as the DuPont formula. This involved breaking down items such as plant and other fixed investment items, as well as amounts tied up in working capital in various categories such as raw materials, work in process, finished product, accounts receivable and required operating cash balances.

Brown’s complete formula was displayed in a 1950 American Management Association publication.

Following the duPont family investment in General Motors Brown pioneered budgeting as CFO at the automaker. Brown implemented a flexible budgeting system by 1923, describing his system in a series of three articles on pricing and budgeting procedures published in early 1924. In his own words in a 1928 monograph published by the U. S. Chamber of Commerce, Brown said: “Forecasting and planning is the essence of modern-day business management.”

1922: J.O McKinsey publishes Budgetary Control

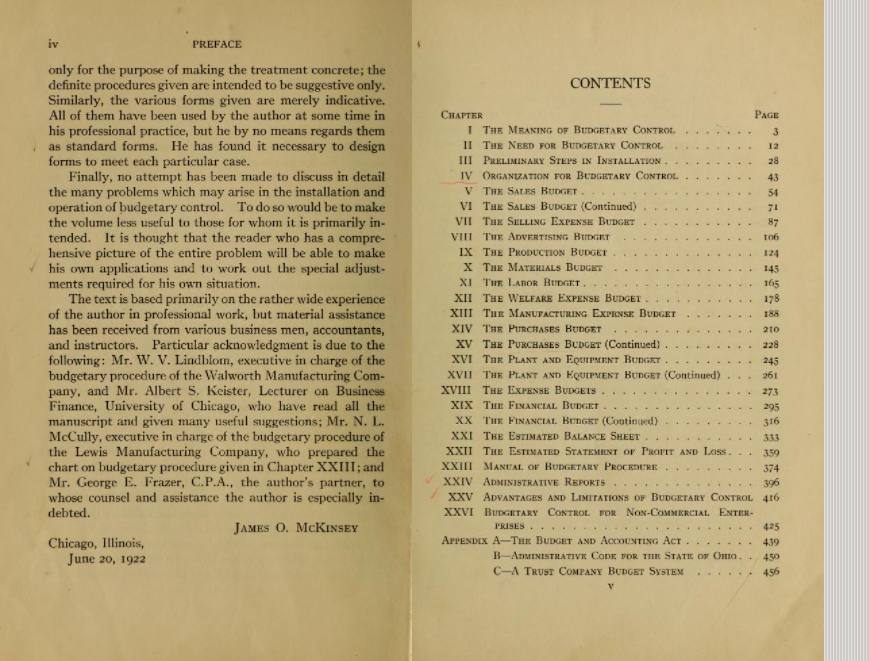

With almost parallel timing with the frenetic activity happening at GM, in 1922, a seminal book on business budgeting by J. O. McKinsey, dropped. McKinsey went on to become founder of the famous consulting firm which bears his name, and a faculty member at the University of Chicago. But his book, Budgetary Control which appeared on June 20 1922, established McKinsey as the father of business budgets. McKinsey wrote in his preface: “Although much has been written of budgetary control as applied to particular phases of business, this is the first attempt, so far as the author is aware, to present the subject as a whole, and cover the entire budgetary program…It is the purpose of these chapters to show that the principles of budgetary control are as applicable to the individual business units as to the governmental unit, and to explain the method by which these principles may be applied.” The book contained no less than 26 chapters ranging from the Sales Budget to the Advertising Budget to the Estimated Statement of Profit and Loss.

Some of the future challenges for business budgets were already signaled in the book. McKinsey argued for instance that “mere study of past records is inadequate”. He added: “The past is gone and cannot be changed. It is only future operations over which control can be exercised.” This continues to be a source of contention for business budgets today with a move still going on towards looking forward and using real-time data rather than solely making forecasts based on historical data. In 1945, Budgetary Control was included in a list of the twelve most indispensable books in the field of management.

The concept of business budgeting continued to spread from the embers at the melting pot at GM. Budget fever reached a peak at the first International Discussion Conference of Budgetary Control (Geneva, July 10 to July 12, 1930) under the auspices of the International Management Institute. Papers presented by business leaders from the US, Canada, the UK, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and France. The conference saw 200 delegates from 27 countries in total.

1960s-70s: The successor to McKinsey: Marvin Bower

The successor and student of McKinsey was Marvin Bower who continued his budgeting evolution. Bower eventually led McKinsey for 17 years and was heralded as the firm’s modern founder. Bower went on to advise the US Government on its budgets, showing how the business world now held the upper hand in best practice. At the 1976 congressional Concurrent Resolution on the Budget, Bower traded on hard won experience of business budgeting, telling congress: “Economic reality dictates that no individual, family, business or Nation can long endure when it makes expenditures for goods and services that are beyond its means to pay for.” He also lamented attempts at forecasting as doomed to fail and made early appeals for what would later become known as scenario planning. Bower told Congress: “To try to influence the future you must forecast what it might be if you don’t act. But I must say, and you can check me two years from now, it isn’t going to happen the way you think it is going to happen. The record of controlling the future is miserable.”

1987: the launch of Excel

The next major change in the history of budgeting did not involve an individual, but technology. In the 1970s and early 1980s, financial analysts would spend weeks running advanced formulas either manually or (beginning in 1983) on programs like Lotus 1-2-3. The launch of Excel in 1987 finally allowed budgeting including complex modeling in minutes. Most users know that Excel can add, subtract, multiply, and divide, but it can do much more with advanced IF functions when coupled with VLOOKUP, INDEX-MATCH-MATCH, and pivot tables. The pull of excel continues till today where courses on business budgeting describe Excel as vital to the process.

1990-2009 Attacks against budgeting begin

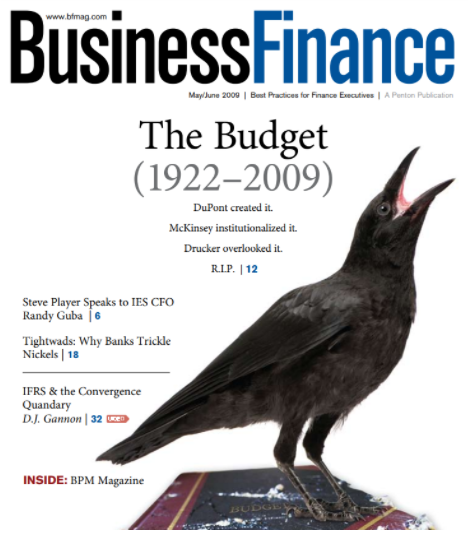

Despite becoming commonplace and simple with Excel, attacks against budgeting gained momentum from the 1990s. Business became ever more complicated and deficiencies became harder to hide. In the June edition of Business Finance, a magazine during this period, Jack Sweeney, now host of CFO Thought Leadership podcast, wrote a cover story pronouncing the “death of the budget” after a relatively short business life ( the budget having lived between 1922-2009). The evidence for the traditional budget’s end included widespread acknowledgment that business numbers don’t arbitrarily stop at year end and well-intentioned annual budgets are out of date sometimes three months after being created. It cited certain companies that had abandoned budgets entirely. Critics of the traditional budget also continue to claim the budget promotes gaming targets.

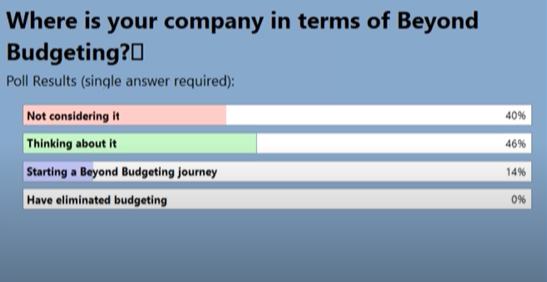

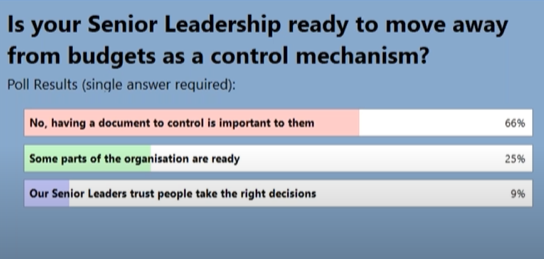

However, rumors of the business budget’s demise were exaggerated. In a snapshot survey taken more than a decade later (in 2021) of a sample of 500 CFOs and FP&As zero participants had actually eliminated budgeting.

In contrast, 66% of finance leaders remain adamant that having a budget document is needed to make short and long-term plans for the success of a business.

The complaints against budgets continue to grow louder as the decades pass. The one that is hardest to tolerate is the inefficiencies forced on talented finance leaders, with the budget by now the domain of newly formed FP&A analyst teams. Studies show that 42% of businesses take up to three months to perform the annual budget process, with a further 42% taking from 4-6 months. Such manual budget tasks (almost exclusively using Excel still today) include 64% of time identifying and correcting errors, 63% manually updating reports and 60% manually collecting and compiling data and 54% tracking multiple report versions. More staggering, this percentage of manual budget-making has more or less stayed the same for the last 10 years according to EY.

2005-present Budgets Strikes Back: Beyond Budgeting

With death averted, businesses began a dedicated movement to change the business budgeting from within.

Enter Beyond Budgeting.

Beyond Budgeting aims to reduce traditional budgeting, and find ways to do business budgeting more frequently. It is the principle whereby companies need to move beyond budgeting because of the inherent flaws, and proposes a range of techniques, such as rolling forecasts and market-related targets in its place.

Robert Kaplan, of Harvard Business School wrote in 2008 to the foreword of Bjarte Bogsnes’ book on the subject, Implementing Beyond Budgeting: “Several companies in Europe and North America have questioned their use of the annual operating budget, a management tool introduced at General Motors nearly a century ago by Alfred Sloan and Donaldson Brown. Although the operating budget was a great innovation at the time, today’s dynamic and highly volatile environment has made an annual fixed operating plan an anachronism. The counterreaction to the high preparation cost, in time and money, of the annual budget and its inflexibility in light of rapidly changing external circumstances and internal opportunities.”

Beyond Budgeting: companies walking the walk

Ivo de Brouwer, finance director Controlling Methodologies, at French food group, Danone, witnessed this drastic shift from traditional to more modern budgeting. He says: “The old ways were still working in 1999. When I started in my career it really was possible for a company to predict the world and what would go on. Even in some circumstances, we could influence the future. In that world it really makes sense that you make a yearly budget and a few times a year you look and see where we are deviating from this budget and ask how do we cope with that?”

By 2016 the yoghurt-maker, like many companies, entered a world summarized by the trendy buzzword: Vuca (volatility uncertainty complexity and ambiguity). They found that the old budget process no longer cut the mustard (or indeed the yoghurt).

De Brouwer says: “We introduced rolling forecasts which meant we are continuously looking one and half years in front of us at what we could expect could happen.We introduced full based scenarios on a best case or worst case situation.”

The next phase to hit budgeting was the fast-paced spreadsheet shocks caused by a pandemic.

COVID-19 and continuing budget shifts

COVID-19 has provided a further boost to rolling forecasts and real-time data over traditional annual budgets. Manish Gundecha, FP&A Director Personal Systems Finance at HP says: “If there is one takeaway from COVID it is that if you have a static budget it becomes outdated as soon as you have an event like this occurring and you are looking around about what to do.”

He cites one example where HP was able to impact its models instantly when the Japanese government set up a tender to supply every high schooler with a laptop during COVID-19. Gundecha says: “That critical mass of people never existed in my historical trends, and I suddenly see about a million to 5 million units being planned for Japan. Suddenly you found HP, Dells and Lenovos of the world are competing for that piece of the pie”.

Discussing Rolling Forecast 2.0 (a COVID-inspired leap further for budgeting for Danone), De Brouwer adds that this involves “combining internal and external data to a greater degree, empowering individual countries in setting targets, and increased focus on scenarios and non-financial data.” He cites the importance of non-financial events as equally important today, in a way Sloan or Donaldson’s budgets never imagined. In one case, an activist investor in Morocco rather than a strictly financial blot, changed the Danone budget. “This issue really blew up into social media, and within one year we lost half of our business within the country.”

COVID explosions continue to affect budget sheets. Michael Tweedie, former Senior Director Global Finance at the LEGO Group (now at Pandora), built up new blocks for scenario planning as a result of COVID-19. This led to economic uplifts, including reinvesting travel savings into working from home equipment, supply changes to off-set restraints and underwriting support for the Black Lives Matter campaign. Amwell, a telehealth company saw its FP&A team ramp up services in the US when COVID-19 limited access to physician care, involving modeling use rates based on 57,000 doctors delivering care.

Conclusion

In 2022, the pendulum has swung back to budgeting as a core business tenet. Universities, online courses and business leaders preach the importance of budgeting deploying Excel, but with a demand for less manual waste and more strategic emphasis on value creation. David Lawrence Ramsey, an American personal finance personality and businessman puts the alternative to having a business budget simply. “The alternative to a budget is to just try to outearn your stupidity. [Without a budget] you can just try to have so much money coming in that all the chaos coming out is okay.”

Budgeting from its earliest origins, and despite its flaws, is an antidote to chaos by funneling cash and investment in the right places. The budget continues to be a blunt but powerful instrument to ensure money gets where it is needed most in a business. That simplicity keeps it alive but further tweaks are always on the cards.